Curious about what it takes to make the transition from letterpress printing as a hobby to a career? We chatted with some inspiring printers who have made the leap from hobby printing to either full or part time printing. For some, the plunge was just natural; it came to them the first time they ran the press, for others, the story is a serendipitous chance of events. We gathered some of letterpress’s best to give their testaments to the alluring power of printing. Read their stirring stories and then we’d love to hear in the comments section about what it was that made you want to take the full plunge into the world of letterpress!

To be perfectly honest, when I first got into letterpress, it was on a whim. I am a graphic designer and have owned a boutique design firm since 2003. Chris (my husband) is a project manager at a software company. We both thrive on creativity which leaves us short on time and too many expensive hobbies.

In 2010 I planned a family trip to Santa Cruz for the week. Other than going to the Monterey Bay Aquarium we made no other plans for our trip. On the way to the airport we were brainstorming ideas for a new business that Chris could do on the side; something creative that he could make his own and be profitable at the same time (as a way to balance these expensive hobbies). I threw out the idea of letterpressing. A friend of mine had recently purchased a table-top press and I was very interested in the process. Chris instantly loved the idea, so we hashed out the details over the course of our Santa Cruz trip and upon our return we began searching for a table-top press.

We ended up purchasing a C&P Pilot Press in July of 2010. The press arrived refurbished in November of that year. We knew very little about printing, but Chris tirelessly researched the ins and outs of printing so it took him no time at all to realize we needed to contact Boxcar for a base among other things.

By February of the following year we had our website up and were getting letterpress inquiries. It only took us 2 or three jobs to realize that we loved the process AND we needed a bigger press!

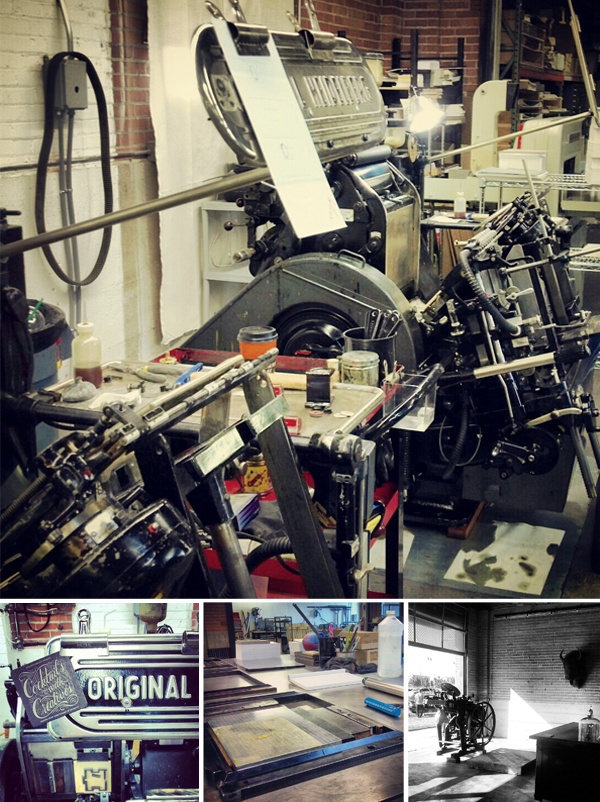

We came in contact with a wonderful man in Oklahoma who sold us our C&P 8×12 old-style press in August of 2011. Little did we know we would be making the trip two more times to pick up a Heidelberg Windmill 10×15 and eventually a 14.5×22 C&P!

Once we had 2-3 jobs under our belt we were hooked, but I will admit we were VERY nervous each time a new job came in. There was a big learning curve to printing beautifully: from packing, to platemaking, inking as well as learning the quirks of each press. It was a bit daunting, but we knew we had to continue taking on the work so we could become more comfortable with the process. Our part-time shop grew very quickly, at times it was too busy! I learned to dial back the marketing slightly so that we could maintain a comfortable stream of business. Chris and I enjoy our day jobs, so we are happy with our part-time status. Do we hope to go full-time in the future? Absolutely, but for the time being we are happy with things as they are.

We started Wishbone Letterpress because I lost my job, and was unable to find a decent paying job. I had been commuting to NYC from the Hudson Valley, and we didn’t want to move to the city, and I was exhausted from commuting for 5 years.

My husband still has a full-time job, and he helps me at night and on weekends. But I started Wishbone Letterpress full-time right from the beginning. I was laid off from my job doing design and animation for a national morning television show. We were taking letterpress classes and researching business development while I was still working, but hadn’t planned on starting a letterpress business so soon. Local jobs were scarce so we figured it would be best to start our own business. After the first class that we took at the Center for Book Arts we fell in love with the process, so it was an easy decision.

I think letterpress found me more than I went looking for it. I had learned some of the most complex motion graphic programs with a career in Los Angeles working at Geffen Records and then developing the DVD for MGM assembling over 5000 DVD’s including the James Bond collection but I missed something. I’m what I call a “designosaur” a graphic artist from pre-1985 before the Mac was introduced – someone who used T-squares, triangles and wax machines. I missed using my hands and having skills that everyone with a computer didn’t think they could do. I missed the days when most people didn’t know what Helvetica meant. Being part of the letterpress community now I feel like a true craftsman again. Every time I pull out my pica pole or tweezers that I’ve owned for 25 years, I get a sense of accomplishment and nostalgia that hitting the print button on the keyboard couldn’t do.

There are two major aspects of a business: producing goods, and selling them. In the context of letterpress, producing is the fun part―printing is why we got involved in the first place. Actually turning what we have made into a living can be an entirely different matter. One danger is to minimize the importance of this second aspect of business: ‘When they see my beautiful work, it will sell!’, or ‘I can sell online―the world is my market!’ However, the world―and especially the internet―is a noisy place, and it is hard to be noticed at all, let alone make an impact.

One of the top marketing minds in the world, Terry O’Reilly, recently pointed out that some of the most successful brands have become that way by focusing, not on what they sell, but why they are in business. And in letterpress―where anyone with a computer can order a plate and crank out thousands of great-looking impressions―the “why” is vital. Ask yourself “why do I print?”, “What makes what I do different from everyone else?”

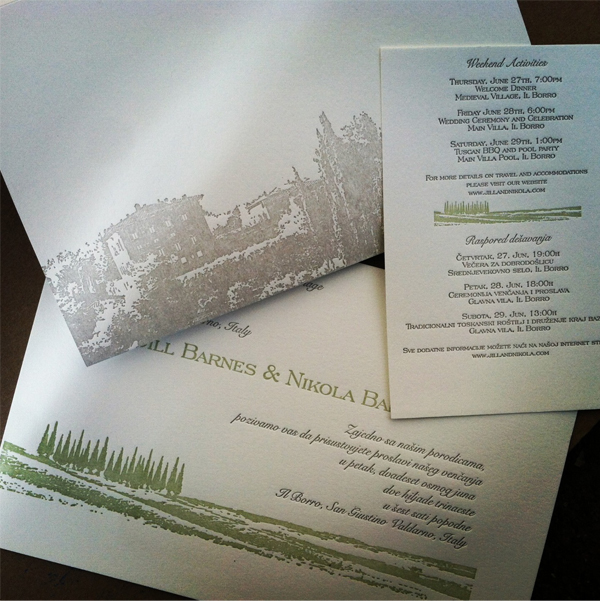

In the case of Sevanti Letterpress, our “why” grew out of an already-established business: vintage fountain pens. My wife, Michele, had purchased a fairly expensive greeting card for a friend with her usual care and thoughtfulness. But when it came time to write the message, she was disgusted to see the ink from her favorite fountain pen (a Parker “51”, which writes with a relatively dry line) bleed through the paper, ruining it. The ensuing conversation, edited for family viewing, went something like: ‘If only there could be a line of high-quality, classically-designed cards, guaranteed to be fountain pen-friendly. Wait a minute! If you want something done right, do it yourself!’ And a major part of our “why” was born.

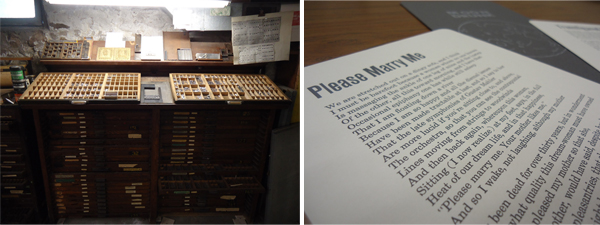

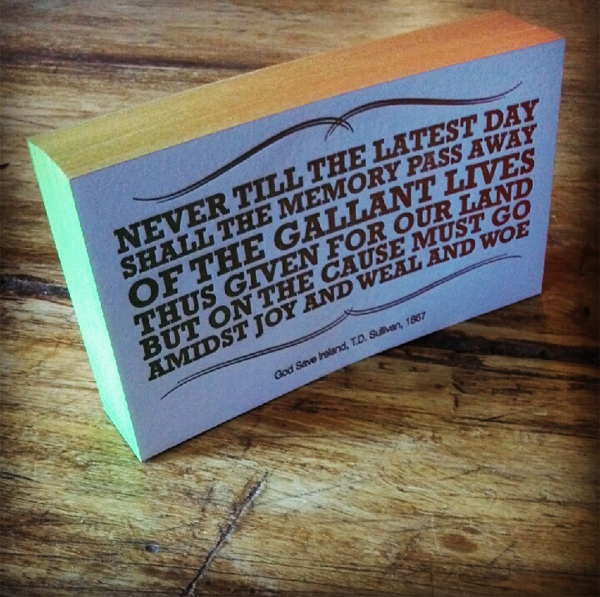

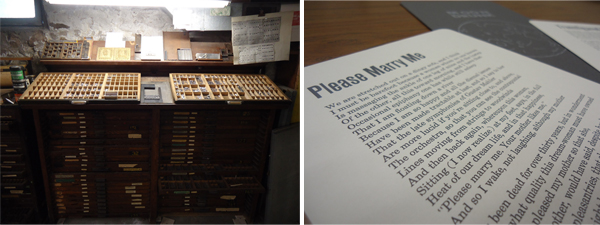

The other facet of our “why” stems from our love of classic typography and design. No funky angled printing, multiple colors, or 1950s clip art here! All of our printing is done with movable type, and with original cuts; white space rules. Every card has an enclosure explaining the origin of the graphic and, whenever possible, the location it can be found in century-old specimen books. While this limits us to some extent, it also appeals to an enduring, and literally ancient, aesthetic. And it marks us as different.

Once you have a “why”, trumpet it everywhere. In your logo, on your website, in your email signature line, on the back of everything you print. Having that “why” will make you stand out, and will also be a constant reminder of what makes you different, and better, than everyone else. And in a noisy world, that will go a long way towards being noticed.

Of course, this all takes time to accomplish. Many years ago an experienced entrepreneurial friend of mine told me that, when starting a business, “don’t expect to make any money for at least two years. And even then you will be working like a dog, but at least you won’t be broke.” So don’t quit your day job.

It may be tempting to lease out the shop space of your dreams, surround yourself with type cases and presses, and revel in the printing life. But remember, dream shops like you see in online photo galleries have taken lifetimes to build up, and at great cost. If you can sell what you print out of your living room―or in our case, off the dining room table―then do it. If you go into debt to start up, then you don’t really own the business, your bank does. If you expand when you can afford it, and only as much as is safe, then the result will be a stable and established business, wholly owned and controlled by you.

Printing doesn’t require a huge infrastructure, and if you keep your eyes open you might pick up equipment for a song. Shortly after finding our press, I struck up a conversation with a “living history” exhibitor at a local museum. “You should talk to our registrar,” he enthusiastically stated. “The basement of one of our buildings is full of donated printing gear we can’t use, because it is out of our date range!” Several sweaty afternoons later, and after a donation of some nice writing boxes and implements that were in the appropriate date range, we had a small printing shop full of type, furniture, and the paraphernalia needed to print anything our hearts desired. So ask around. Attend the local wayzgooze. Make friends with printers. You never know with whom you can trade equitable favors. The details of what you print, and how and to whom you sell, will vary depending on your location, your market, and your circumstances. But the founding principles―the “why,” and the financing― are what will make a big difference between a zealous hobbyist and a lasting professional.

I still distinctly remember the night after my first letterpress class at the Center for Book Arts in New York City. I met my husband for drinks nearby and declared, “Oh man, I’ve finally found the thing that I want to do!” It really was like a light had been turned on in my life, and everything was suddenly illuminated. I loved the meditative process of setting type, as well as the historical anecdotes our instructor, Barbara Henry, told as we worked. The smell and patina of the lead on my fingers reminded me of days spent in my grandfather’s shop as a child, and the presses…well, the presses completely fascinated me. What I loved best, though, was the sense of accomplishment that I felt after pulling a print—the instant gratification of it, combined with the knowledge that every impression was slightly different. I felt humbled and elated by the process.

I think I knew, even at that early moment, that I would end up as a printer. I was lucky enough to land an apprenticeship in the garment district at a commercial shop, where I quickly learned the difference between futzing around with type and making sure that stationery for Versace and the New York City Ballet looked its absolute best. What surprised me, though, was that I loved all of it. For me, the art was in the process, not the end result. It didn’t matter if I was printing for myself or the fanciest society soiree; when I was printing, I was happy. Almost immediately I started thinking of how to make letterpress my full time job.

There were many schemes that were tried and discarded, including working as an under-the-table Windmill pressman at a large commercial print shop on the docks in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The press was in terrible shape and most of my work consisted of die-cutting and numbering, which I hated. Through these piecemeal jobs, I was learning that what I wanted to do was all of it. I wanted to design beautiful things and print them, too. Maybe it’s because I learned on a Windmill, a more traditionally commercial press, but it never occurred to me to just get a C&P and make some stuff in my spare time. I went from working for someone else to dreaming of my own Windmill, and my own press.

My husband and I began to toss around potential names. We had already planned to leave NYC, but hadn’t yet set a date. I scoured Briar Press looking for a Windmill to call my own, but everything was still very hazy and dreamy at this point, an idea but not an actualized one.

On our first wedding anniversary, all of that changed. I’d decided on the name Shed Letterpress for my business about a month before, and my husband surprised me with my very own letterpressed business cards as my paper gift. He had designed them and had them printed by my former mentor, Tim Chapman of Press New York. For whatever reason, the cards made everything very real. I bought a Windmill in Pennsylvania within the month and, since there was no place to put it in our third floor walkup, we picked up speed with the move out of the city. I quit my job and, four months later, we found ourselves in North Carolina and Shed Letterpress was born.

The original Shed was hastily picked more for its convenience than its appeal. It was a flex space in a storage facility that one of my clients described as “kind of sketchy.” For the first year back in NC, I printed when I could while working other odd jobs and getting settled in my new city, but I knew that I had to find a better spot.

The decision to go full-time with Shed Letterpress was really just a matter of finding the right space. Once I found my current studio, in the heart of downtown Durham with a wall of windows, I knew that I owed it to myself to give Shed Letterpress everything I had. It was actually scarier, to me, not to go ahead and do it! My husband, as always, was incredibly supportive of my venture and agreed to float me for a while until I had things figured out. In hindsight, I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, and am still having “duh” moments every day, but I wouldn’t trade the experience for the world. Ultimately, what made the decision easy for me was the unwavering support of family, friends, and letterpress colleagues that I’ve met along the way. Knowing that there was always someone on the other end of the phone, or even just asking the same question as me in a Briar Press post, made me feel less alone and more able to take on the crazy responsibility of becoming a small business owner. I’m three years in now, and going strong!

I was looking for a creative outlet to provide an escape after my corporate workday. Initially, I had been searching for a calligraphy class – something I could practice at home without designating a ton of space. But alas, calligraphy was not being offered that session so I enrolled in another class – Intro to Typography, a beginners letterpress course. Our first project was to sort a bunch of type into a California Job case. I was instantly smitten.

I knew really early on that I would be growing a business out of my passion for letterpress. The story goes: within 10 minutes of my first letterpress class at the Genesee Center for Arts and Education, I had fallen in love. By the end of the second class, I was dreaming if quitting my day job. 6 months later, I did. For me, the excitement is in the creation. I knew I would have to sell my work in order to pay for more creation. And I was OK with that because I was producing far more than I could ever keep!

As with every successful letterpress project, start from the end and work backwards. Make a business plan. Ask yourself, where do you want to end up? Then list out the steps you need to take in order to achieve your goal. It doesn’t have to be a super detailed, even just a short list outlining your goals and expectations can be really helpful. Defining what you want your business to become is the best way to manifest your goal. And as a bonus, you sound smart and confident when you talk to people about your new business because you’ve taken the time to establish a foundation.

My transition from hobby printer to full-time printer happened about two years ago but it was about ten years in the making. I took my first printing classes as an undergraduate student, continued dabbling throughout graduate school, and then took my first letterpress printing course at The Center for Book Arts (NYC) in 2010.

I knew I wanted to do letterpress full-time when I realized two things: how happy doing it made me feel, and how happy a custom piece of stationery made my clients feel. Taking the plunge, for me, involved an uncomfortable balance of desire and uncertainty, but it was a willingness to challenge myself that ultimately set me in motion. Having studied environmental design, then landscape architecture, I used that formal education to develop my first projects. I still try to incorporate artwork involving architectural elevations or place mapping whenever appropriate. And of course, as a print maker, the precision skills do come in handy.

For what it’s worth, I think that when transitioning into anything new, it’s helpful to see everything you’ve done as building blocks for your future.

In my case, clarification came in an unambiguous and unwelcome form—I was laid off from my job in February 2009 as the economy was tanking. I had been running a small letterpress shop for a design firm in Birmingham, Alabama whose main clients were a large regional bank and various real estate developments. Not the best clients to have at that time.

Had I not been laid off from my job, I’m not sure if I would have ever gone out on my own. Health insurance and a steady, decent paycheck are difficult things to turn one’s back on. Fortunately (or unfortunately), all I know how to do is run a letterpress so it made the next step undeniable. I looked for the cheapest space available, which was a dingy storefront that needed a ton of work but only cost $350 a month. I spent six weeks making it into a habitable printshop and had $6000 to my name at the end of it. I figured I could last 3 or 4 months without earning a dime, longer if I slept on the printshop floor. Business came slowly at first but I made enough to get by and keep the doors open. Word of mouth does wonders. I am now entering into my fifth year of business and am grateful every day for my good fortune.

I am a true believer of serendipity; I think things happen for a reason, that if you’re listening, your life’s work is calling out to you like a soul mate. Print work has been following me around for most of my life. As a child I would regularly skip school so I could go to art school with my mom, who was attending the Museum of Fine Art school in Boston and later received a Masters in Printmaking from Tufts. Her studio was my happy place… I was always enamored by the smell of print: fresh sawdust in the wood shop where plywood became relief, the earthy smell of ink mixed and spread, turpentine in the air everywhere.

(photograph courtesy of Green Door Photography)

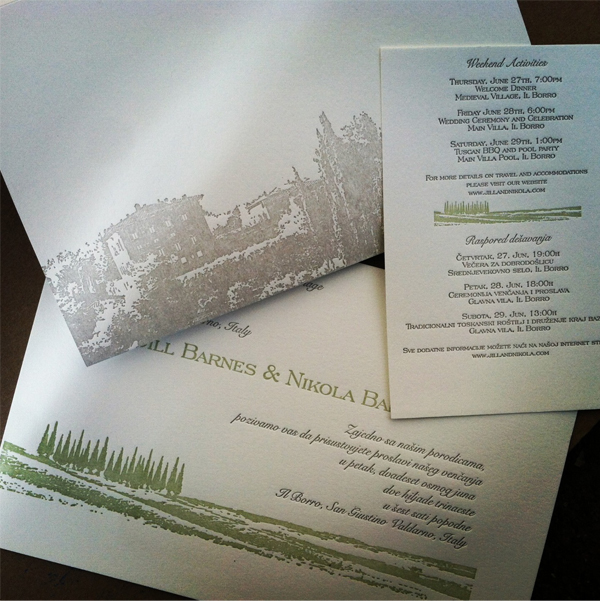

I went off to college for creative writing and back again for graphic design. And after struggling to find my place in the graphic arts world, I worked for a newspaper and a great little magazine called MaryJanesFarm, where I was exposed daily to the cast iron trappings of a bygone era. During that time, I got engaged and discovered letterpress printing. I hand illustrated my wedding invitations and had them printed in Provo, Utah by Bryce at Bjorn Press, who was incredibly generous with his time and knowledge, spending what seemed like hours on the phone discussing the ins and out of my project and the art of letterpress. He said if you are going to get into letterpress you’ve got to get a Vandercook Proof Press and something about if you could find a number 4, you’d be set. I loved, loved, loved the way my illustrations looked (and felt) pressed into that soft cotton paper… so I followed his advice posthaste. I found one on ebay for what now seams like a steal in “perfect working order”. It arrived from Baltimore on a freight train in a huge crate. I plugged her in, inked her up, turned her on, and with paper in the grippers I rolled the cylinder over some type I’d found… and wala! … nothing! (or at least, nothing to write home about). Well, there were a few things going on there…first and foremost, I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, and there were in fact several parts missing or broken (so much for perfect). That’s when I found Fritz at NA Graphics. Through phone conversations and emailed photos, Fritz was able to diagnose and treat my ailing press (he is a true hero of letterpress… and there are many more out there that if I mentioned them all here this would be a hundred pages).

(photography courtesy of Green Door Photography)

A month or two later, I printed my first set of wedding invitations for some friends. It was bliss: in my garage, radio blaring, dancing a little as I rolled the cylinder back and forth getting into a rhythm. I look at those invitations now and I see a lot of “mistakes” (you know the regular suspects; too much ink, too much impression, rollers in need of replacement etc.) but I also see a girl who was driven to figure something out by a passion that she could at that point just barely taste, but she knew it was good. From that first job, I knew I wanted to print full time, but there were things that had to be done first, like learn everything I possibly could about letterpress, get as much experience as I could, start a family and begin raising two small children to name a few.

By 2007, totally over the ever changing climate in my garage I was ready for a change. I attended the National Stationery Show in New York as an artist with my youngest child strapped to my chest. Needless to say I was in awe of and I’ll admit pretty intimidated (still am!) by what I saw there and decided I wanted to bring all that glorious paper and design to Missoula, Montana in the form of a brick and mortar store.

Literally the day after returning from NY, I ran into Amy, then just a casual acquaintance, at a local restaurant, where we decided to open a store together. The store would bring together beautiful handmade cards and stationery from around the country while featuring my Vandercook #4 proof press as part of the retail environment. Our customers could watch while we printed anything from greeting cards to wedding invitations right there on the sales floor or through the large picture windows that looks into our tiny pressroom from the arcade of our historic building. That was five years ago this June. In that five years we have had to put a lot of focus on the retail end of our business, but in the meantime we have been building up our letterpress forces in our 1,000+ square foot basement. Amy and I are a great design team; she’s the people person and I tend to communicate better with large machinery… and she fully supports my 1,000 lb habit. The basement studio now houses a beautiful hand painted peerless gem guillotine paper cutter, 2 C&P,s and our newest edition, a Heidelberg Windmill. And this May, after five years of attending NSS as buyers, we will be exhibiting for the first time as a part of the Ladies of Letterpress booth (booth #2374-80!).

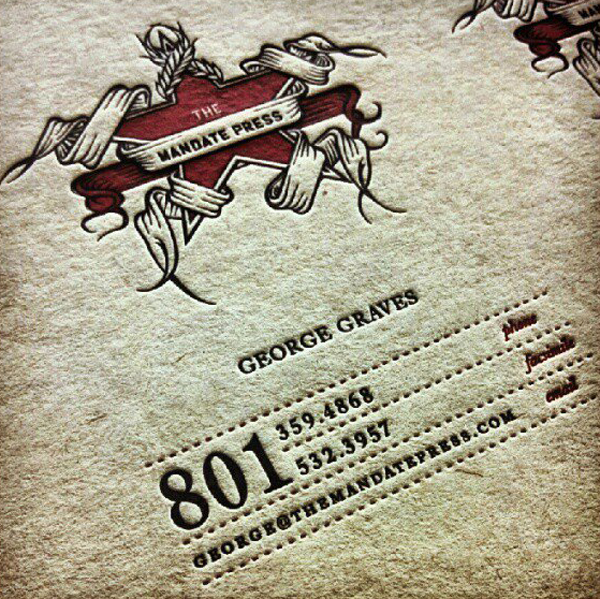

Crosshatch Printing Co. was formally started up in 2012 as a collaboration between myself and my mom in Raleigh, North Carolina, but I first got into letterpress out in San Francisco, California in 2009. As a birthday present for a close friend I tracked down an old Kelsey 5×8 platen press in Los Angeles and hid it in the trunk of my car for the next couple months. I’m an architect by training who fancies himself a graphic designer and had no idea that the cast iron weight in the back of my Honda would become a mild obsession for the next four years. After catching the letterpress bug I moved to Philadelphia and eventually found a C&P Pilot in Washington, DC and started working out of a small studio on the third floor of a rented apartment. My first paid job was a series of business cards for a photographer in town, and since then I’ve worked on a variety of wedding invites, greeting cards, Christmas ornaments and others.

After a cup of coffee one of the first things I do every morning is to get on the classified section of Briar Press and see if there is any old equipment that needs rescuing. I was lucky enough to find a C&P 10×15 in my hometown of Raleigh, NC a couple of years later and with the help of family, friends, and forum searching moved it into the family garage. Fast forward a couple more years and a job change, and I was back in Raleigh and looking to get the press up and running. With all of the equipment finally in one place, my partner and I thought it was time to finally move from hobby to a part-time business and Crosshatch Printing Co. was born. We currently share a studio/shop space with The Raleigh Architecture and Construction Companies in an old tire shop and have been continuing to work and collaborate with clients and artists in the area.

For others wanting to get into the letterpress business, I recommend spending time finding people you respect to work with and taking on jobs that you’ve never tried before. Every job presents its own challenges, and even a routine run can turn into hours of troubleshooting, head scratching, and pacing. Keep patient, phone a friend, search the forums and remember that each challenge is a lesson learned for the next job. We’ve made a habit of constant experimentation in our studio and use new jobs as a way to test out techniques and different mediums. We’ve been lucky to work with talented individuals that trust us and get most of our inspiration from healthy communication during all aspects of the project.

My mother was the village librarian in Parma, Michigan, where I grew up, and I was always surrounded by books. There was a book, a history of the village called CRACKER HILL CRUMBS and I remember my mother telling me that the Friends of the Library owned the plates from which the book had been printed. They were, stereotyped plates (or perhaps photo engraved cuts) taken from forms built up out of linotype slugs. I didn’t know the exact name for those things when I was a little boy, but I do know that one of my earliest memories of the library was thinking about how this thin little volume existed, somewhere, in the form of 196 metal plates on galleys in Brooklyn, Michigan at the Exponent Press. So that was always there, the idea that books were made, that metal and pressure and gears were involved.

I did not get into the whole thing as part of any clear plan. I just couldn’t remember a time when I wasn’t fascinated by printing and by how books are made. I gave different people different explanations for why I had bought the press, but really, it was just something that I had to do. I didn’t tell lots of people about it at first, and when we had friends over for dinner one night I invited them down to see the press. My friend Ben, who I had known by then for 7 years looked at the press and then turned around and offered me his hand. “Hi,” he said to me, with a look of amazement, “I don’t believe we’ve ever met before.” That’s how I felt, too. Like, when I bought the press, I was meeting myself for the first time.

My wife and I immediately decided we need to professionalize. We couldn’t exactly believe we had just spent $1200 plus travel on an antique print shop. In 2005, letterpress was still very new as a product. That’s a weird, but true, description. The industry had collapsed by 1993, and in the early 2000s letterpress was as dead as it ever was going to get. There were craft printers in major urban centers, and some shops who still had letterpress equipment, but Martha Stewart (ie the Broad Public) was only just re-discovering the form.

When we set up Manchester Press in 2005, I remember that our Google Ads regularly appeared on the first page of search results for “letterpress”. The broad public was just starting to think about letterpress as a luxury printing option. We figured out how to get plates made at Owosso Graphic (just north of us!), we made some sample wedding invitation designs, got a few clients, and did some jobs. We quickly made back the money on the press.

But by 2006, letterpress shops just started sprouting everywhere. And I realized that I had a day job teaching, a night job writing, and neither my wife nor I had any real design training. I wasn’t always happy with my presswork, and I just knew that we weren’t going to be able to compete with the really great shops that designers were setting up on their own. Boxcar Press, and its amazing products, figured heavily in my decision to pull back from full-time press work. I didn’t want to make an inferior product.

We went from almost full-time down to hobby pretty quickly. I was obsessed as ever with the press, and with learning about type and design, but after the short burst of business we did, I didn’t feel any pressure to justify having a press. I wanted to learn, and to get good at it.

So, I spent time after work on floor 2a East of the University of Michigan Graduate Library where the letterpress printing books are shelved. And I started reading. I read everything I could from Joseph Moxon to Ralph Polk and his textbook. At the same time, my friend Jason Polan was building a career as an artist in New York, and we started developing projects to do together on the press.

When the opportunity came up to drive down and profile Theo Rehak at the Dale Guild, I just did it. I wrangled a grant, drove all day, slept on Jason’s couch, spent a day in New Jersey with a recording device, and wrote for a month. That long essay, “The Last Man for the Job”, wasn’t something I had to develop or think through. It was exactly what I had to say at that moment.

That’s what the press is for me now. I try not to compete with what every one else is doing. I just try to add the thing I can add. I’m not a printer who writes. I am a writer who prints. I like to think that even if I am never a great printer, I’m a pretty good chronicler of the movement because I understand it with a level of detail most other writers wouldn’t have the inclination to acquire.

I try to only do things that I am compelled to do. I try not to do things I feel like I SHOULD do, or that would be GOOD for me, or my career. I try to focus on things I MUST do. Obviously everyone has to eat. I try to diversify my income, I try to follow a lot of threads and see where things take me, I try to keep my options open. But mostly I am stubborn and I want things the way I want them. There was a printing press shaped hole in my life. I filled it. I did what I felt compelled to do.

Ultimately it came down to the fact that there were not enough hours in the day to have another job on top of trying to run a business and get orders out promptly. It got to the point after 6 years that if I didn’t take the plunge or figure out a way for there to be an eight day week, it was going to start hurting working relationships that I have built up over the years. I definitely had enough work to support the choice to quit my other job, and although it was scary not knowing if the good success would continue, it gave me the time to make sure that it did. One of the biggest recommendations I have for people is to grow slowly and avoid excessive overhead whenever possible.

If you’ve got a story about your transition from hobby printer to career pressman, please tell us about it in the comments section below!