In its sixth year of running, we’ve teamed up with amazing young poets, and inspired printers to share with you 2016’s Seattle Children’s Hospital Broadside project in a two-part blog feature. The collaboration of 22 artists and pediatric patients is helmed by poets Sierra Nelson and Ann Teplick of the Writers in the Schools program and the School of Visual Concepts in Seattle. WITS works with long term patients at Seattle Children’s Hospital to write poetry, out of which printers & artists create beautiful letterpress broadside prints. Boxcar Press supports this project with photopolymer plates for the limited run of broadsides. Participating printers share their experiences bringing each poet’s words to life in this year’s edition.

This first installment features six printers who share their printing process and experiences with the youth writers of the program.

Bonnie Thompson Norman Every year, I feel a strong connection to the young person whose poem I print. I know each person who works on these broadsides feels the same way. We don’t always have (or choose to have) the opportunity and/or privilege of meeting our poets, but the bond is a strong one. As the project comes to an end, we all gather for a potluck dinner. All of the completed broadsides for that year’s project are displayed. Each of us reads “our” poem and talks about the process of creating the image, designing the text, printing, etc. The sharing that takes place as we read and talk about our connection to the young person who wrote the poem and our experience in interpreting it for others to see, is a meaningful bond for all of us and each of us…to the writers, the poets who work with them, and one another. It is what keeps us looking forward to coming back year after year. It isn’t just a legacy for the poets and their families. It is our legacy, too.

Here is a video of the creative process for a few of us:

(video courtesy of www.seattlechannel.org)

One last comment on the bond between printer and poet… last year, I wrote a blog post about my young poet who I was able to meet on his 17th birthday. He teared up when he saw how I had interpreted his writing. We met at the Children’s Hospital where he was (again) a patient when I gave him his copy of his poem that I designed and printed. We were both emotional when he saw how I had interpreted his writing. It was so gratifying to see how he appreciated what I felt was our collaboration though we had not met before.

Chris Copley 2016 was my second experience with the Seattle Children’s Hospital poetry broadside project. My 2015 project was both artistically challenging (still a rookie to letterpress, I carved three 10-inch-by-13-inch linoleum blocks to illustrate the poem’s text and images) and emotionally poignant (the poet I worked with, 13-year-old Ahmie Njie, died about a month after I printed her poem). Exchanging a few Facebook IMs with her before she passed away remains one of the highlights of my life.

I liked the idea of incorporating the text of the poem itself in the illustration of the poem, so I planned to do that again in 2016. I worked with a poem by 12-year-old Kayli Jones, a Chinese-born adoptee living with her American parents and three brothers in Idaho. I exchanged a few email questions with the poet’s mom to learn a little more about the poet.

The primary design concept for me revolved around Kayli’s Chinese origins. So I decided to use the poem’s text to represent branches of a Chinese-style cherry tree in bloom. Cherry blossoms are considered a symbol of good luck in Asia, and Kayli’s poem ends on a note of hope and determination to beat her cancer.

I hand-drew the letters of the poem, then ordered a polymer plate from Boxcar. This was my first polymer plate print run, and it worked SO WELL. I couldn’t have been happier. All of my text was printed in black. I then hand-set a tall, thin column of text for the colophon; the form was intended to evoke the look of a column of characters on a Chinese-style painting.

I decided to print the second color, red, using a different technique — pressure printing. I used a print from the first color run to cut out the cherry blossoms, and then glued them onto another print to create the pressure-print “plate.” I used the print with the blossom “holes” as a frisket to mask the speckling you get with pressure printing. Printing the blossoms also went pretty smoothly, although I had to recut the frisket twice to try to get the blossoms the way I wanted.

(An added disaster-turned-blessing: I forgot to bring a linoleum block as required for pressure printing, so I used the backside of a Boxcar base, and the swirly pattern on the base’s bottom side left an absolutely beautiful effect on the cherry blossoms.)

Finally, I added another element, at least to some of the prints: several hand-drawn Chinese-style chops, also in red ink. Two of the chops spelled Kayli’s name in characters reminiscent of ancient Chinese text. I printed them freehand on only a few prints, using an ink-stamp pad because I worried they would distract from Kayli’s poem.

I was really happy with the broadside design and printing, and I felt it represented Kayli well. As much as I enjoy the artistic and technical challenges of portraying a poem, it’s important to me to represent the person whose work I’m illustrating.

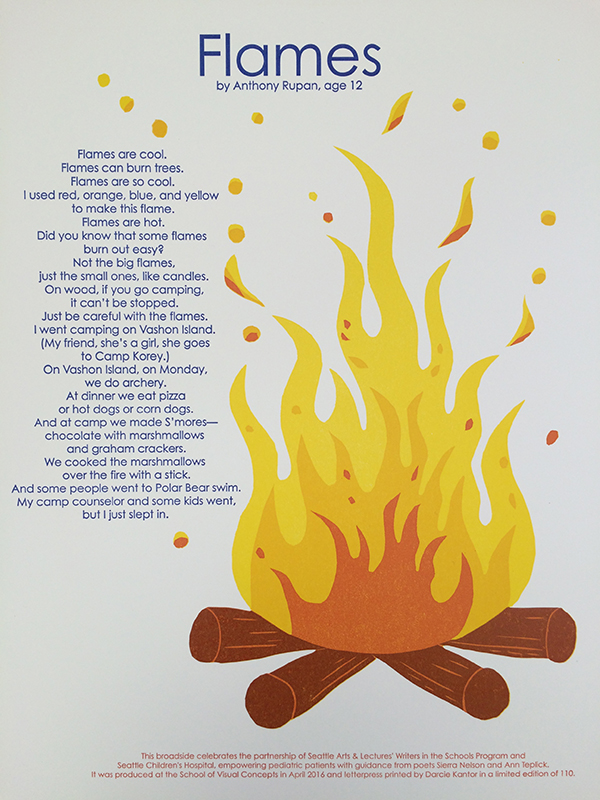

Darcie Kantor It was an honor to be part of the Children’s Hospital Broadside project. This was my second year participating.

For my process I combined Boxcar plates for the poem and did a linoleum block reduction for the fire/flames. It was a fun project to work on.

Juliet Shen The boy who wrote this poem was a registered member of the Swinomish tribe whose lands are north of Seattle on Puget Sound. I had designed a font for the Lushootseed language (indigenous to this area) and asked my contacts in the Tulalip Lushootseed Department to have his poem translated so it could be typeset in both languages.

When it comes to making art work, I am against the appropriation of traditional Native American art styles by outsiders because my research for making the Lushootseed font revealed that the iconic imagery used by Northwest tribes has deep cultural significance. I decided to design to my particular strengths, which are typographic, not illustrative, so I typeset the poem in a shape that I hope looks like an elk to readers. I rely on polymer plates because my primary focus is on typographic design and I need the control that using polymer affords me.

Heidi Hespelt I do want to say that our printing community is amazing! I had a terrible back injury at the end of last year and was pretty much out of printing commission. Amy Redmond offered to do the actual printing for me if I wanted to be involved in the design. She made it possible for me to participate by giving of her time and printing expertise.

Project supervisor, Jenny Wilkson, selected a younger poet for me, not knowing that she chose what was secretly the one I wanted. Serendipity. My poet was Alex Enderle, and the poem was “I Am Me”. Alex was 7 when he wrote the poem.

I think of it as the cupcake poem. I wanted a younger poet because I have a now 5 year old grandson that is a big part of my life and felt like I could probably tune in to what a little guy might find interesting. Bright colors and yumminess that you can see seemed important and I loved what I was able to accomplish with Boxcar plates.

Annabelle Larner I’ve participated as a printer in the Seattle Children’s Hospital Broadside project since its inception about 6 years ago.

Most of my work is all hand done. This year’s project, from April 2016, was printed using a hand-cut wood block as the printing base, with a lightning bolt used as a pressure print. It was printed with a split fountain ink in dark blue, then the final polymer type was printed in red.

Working on this project is extremely rewarding, and also hard. I want to really get into the words of the printer and try to convey their feelings in a way that is not too literal or childish, as I know kids can appreciate darkness, and what they are going through is pretty dark. Sometimes I get to meet the kids and it’s always special. Their parents are often very grateful, and seeing the kids talk about their poems is amazing.

Stay tuned & read on about this amazing Broadside project in the upcoming Part 2. The creativity and intensity of both poets and printers and the dazzling results are why Boxcar is proud to have a part in this project every year.